In the first chapter, Machiavelli begins to lay out his typology of regimes (quick aside, when the chapter is short, we will quote it in full; otherwise, you will need to refer to your own copy of the text):

How Many Are the Kinds of Principalities and in What Modes They Are Acquired

All states, all dominions that have held and do hold empire over men have been and are either republics or principalities. The principalities are either hereditary, in which the bloodline of their lord has been their prince for a long time, or they are new. The new ones are either altogether new, as was Milan to Francesco Sforza, or they are like members added to the hereditary state of the prince who acquires them, as is the kingdom of Naples to the king of Spain. Dominions so acquired are either accustomed to living under a prince or used to being free; and they are acquired either with the arms of others or with one's own, either by fortune or by virtue.

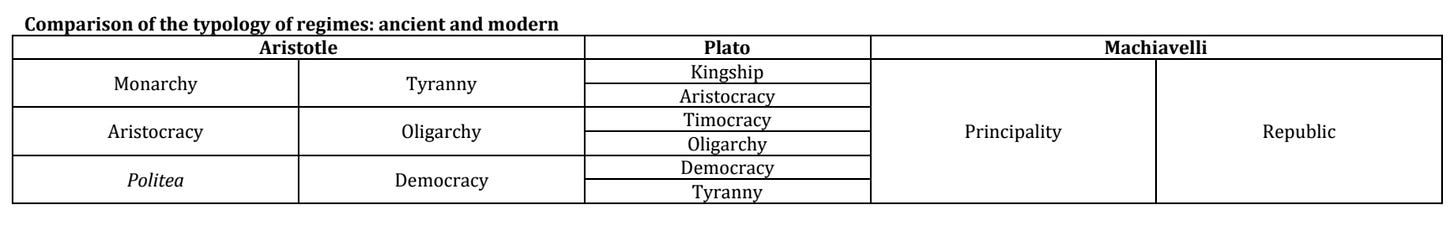

Generally there are two types: republics and principalities. This can be compared to both Aristotle and Plato’s typologies: monarchy, aristocracy, politea, democracy, oligarchy, and tyranny, on the one hand; and kingship, aristocracy, timocracy, oligarchy, democracy, and tyranny on the other.

What is the significance of radically narrowing the bases upon which one distinguishes different types of regime? At part of any answer to this question is that Machiavelli is denying the essential relevance of the end (telos) of the regime. The ends of rule are demoted in importance at the very least, if not dismissed entirely. That the latter has become the case is clear in contemporary International Relations theory, which treats all states as power seeking black boxes. But has our resultant understanding of politics (both foreign and domestic) been deepened by this shift?

Chapter 1 also provides the order of the first part of the work. One can fruitfully compare what Machiavelli says he will do with what he actually does, taking special note of deviations and departures.

Of Hereditary Principalities

I shall leave out reasoning on republics because I have reasoned on them at length another time. I shall address myself only to the principality, and shall proceed by weaving together the threads mentioned above; and I shall debate how these principalities may be governed and maintained.

I say, then, that in hereditary states accustomed to the bloodline of their prince the difficulties in maintaining them are much less than in new states because it is enough only not to depart from the order of his ancestors, and then to temporize in the face of accidents. In this way, if such a prince is of ordinary industry, he will always maintain himself in his state unless there is an extraordinary and excessive force which deprives him of it; and should he be deprived of it, if any mishap whatever befalls the occupier, he reacquires it.

We have in Italy, for example, the duke of Ferrara, who, for no other cause than that his line was ancient in that dominion, did not succumb to the attacks of the Venetians in '84, nor to those of Pope Julius in '10. For the natural prince has less cause and less necessity to offend; hence it is fitting that he be more loved. And if extraordinary vices do not make him hated, it is reasonable that he will naturally have the good will of his own. In antiquity and continuity of dominion the memories and causes of innovations are eliminated; for one change always leaves a dentation for another.

In the second chapter, Machiavelli says that hereditary principalities are the most difficult to lose, because “the natural prince has less cause and less necessity to offend; hence it is fitting that he be more loved.” But this gets revised somewhat in the sequel, chapter 3. As Machiavelli discusses it there, men willingly change masters out of the belief that they will fare better; however, they will do so again if the old prince (or one of his line) still lives. The first problem is a problem for the old prince; the second problem is a problem for the new prince. But note, all kingdoms, old or new, are easy to lose because of the nature of the people.

When you are reading Machiavelli you should always be thinking and asking, “what is the lesson here and for whom is it intended?”

Here the lesson is to the new prince. First, if either the old prince of one of his bloodline will inevitably serve as a rallying point for a rebellion, what should you do? Extinguish his line so there is no legitimate alternative to your rule. It is because of the left over relatives that hereditary regimes are so easy to keep (at least within the family).

The second lesson is to promise as much as you want to or think you can to those who will help you to acquire power. (Think of every candidate for office in the US.)

The problem here is that you owe something to those who do so; you owe something to those who help you get into power and so you do not think you can treat them poorly. What happens as a result? They get rid of you, then you come back and wipe them out.

So the question is, if you know that your ‘friends’ will inevitably turn on you, but you feel obligated to them for their assistance and so do not wish to kill them, and you know that when they depose you, you will no longer owe them, the question is, what do you do? What should you do?

You get rid of them the first time! Why wait for them to turn on you; why wait until you get back; kill them from the outset, as soon as you have power – you should recall that political allies are not friends.

Notice Machiavelli doesn’t simply come out and say this, he makes you think it. He makes you figure it out and, thus, you cannot become indignant, because you are his accomplice. You are the one who dots the I’s and crosses the T’s.

The fact of the matter is that a new prince will always hurt those whom he comes to rule. This is because changes of any kind always harm some of those who benefit from the status quo. So how does one overcome this problem?